There's No Place Like HoMu

Noterdaeme and Isengart share stories about running a museum in their apartment.

Recorded in Brooklyn, May 2006

Daniel Isengart: The Homeless Museum in Brooklyn has been open for about a year. With the exception of the hot summer months, we have held open houses at the Museum about every four weeks, on Sundays. Let's talk about our experience of receiving total strangers in our home on a regular basis.

Filip Noterdaeme: Holding "Open Houses" is my favorite part of the whole operation. Granted, there is a bit of stress involved in the hours preceding the openings, as we have to set everything up, prepare the food for the Café and make sure that all the interactive exhibits are working properly. Plus, there is always some anticipation as to who will show up. But once we're ready to go, it's a smooth ride. HoMu BKLYN really is the fulfillment of a fantasy of mine: to be surrounded by art in my own home and witness an audience's reaction to it. Since the Museum never matches what people expect it to be, I get to see their sense of wonder and surprise, which I enjoy tremendously.

DI: Perhaps we should mention that you are spending the entire time of the opening lying in bed in the so-called Staff and Security Department, which visitors enter towards the end of the audio tour.

FN: Yes. During the first half of the day, I usually pretend to be asleep, which is hilarious because you always announce to visitors that I am "working."

DI: Sometimes people tiptoe back out of the room, telling me in a whisper, "the director is asleep." I always correct them, saying that you are working, and encourage them to go back into the room and look at the $0 Collection displayed on the loft. But eventually, you always "wake up" and engage in discussions with visitors about museum culture. I call it "the director is holding court."

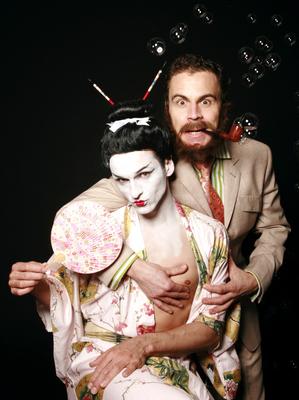

FN: People enjoy it so much they don't want to leave! Since I am in character, impersonating the director of a museum that is really fictitious, I can be as eccentric as I want. We should mention that you are also in character, posing as Madame Butterfly, HoMu's Director of Development.

DI: I'm wearing a kimono and geisha wig. Visitors are somewhat startled when they come in and see me like this, especially since I am acting completely normally. It's an odd contrast. They never know if they should react to it or not. What happens when people first encounter you in bed?

FN: Most people behave as if I had caught them prying into my private life. All of a sudden, they realize they are the ones who are being watched. It is a fascinating moment to observe, because it makes you understand just how powerful our sense of privacy really is. Basically, people don't want to intrude. I quickly dissolve their discomfort by welcoming them and striking up a conversation. I behave as if receiving people in bed were the most normal thing, and what started as an awkward situation soon becomes a cozy sit-in with strangers.

DI: Tell us about some memorable moments.

FN: One day, a young mother breast-fed her baby in front of me and performed a diaper change while we were having a conversation about contemporary museum architecture. Of course, I had to have my picture taken with the baby!

DI: Was that before or after the diaper change?

FN: All I can remember is thinking about how much shit museums have to absorb from architects!

DI: And they are disposable, too! Who else crawled into bed with you?

FN: A Polish TV reporter! She giggled throughout the filmed interview and played footsy with me. Most of the time, though, visitors just sit around my bed and we talk about art and what's happening to our museums. I encourage them to debate what we are to think of a society whose major cultural institutions claim ethical integrity while deliberately excluding low-income citizens through their forbidding ticket prices. To lighten up some of the more serious conversations, I blow soap bubbles out of my pipe or have Florence, our "Director of Public Relations,'' interrupt us with a comment.

DI: We should mention that Florence is a stuffed coyote we ordered from a taxidermist.

FN: I always introduce her as a distant relative of the coyote Joseph Beuys used in a performance in NY in 1974 (I Like America and America Likes Me). She is positioned in front of a microphone that is connected to an amplified, hidden tape recorder, which I can activate from my bed to make her speak.

DI: Tell us what she has to say.

FN: I'm using audio clips from a recording from an early Nineties' conference focusing on the legacy of Joseph Beuys. There is a statement by Lawrence Weiner ("There is nobody walking away clean in this world any longer") and a lament by Huston Smith finishing with the exclamation that "we're a flawed species!" That's my favorite line on the tape.

DI: You once told me of the experience that inspired you to receive visitors in bed in the first place. Tell us about it.

FN: A few years ago, I had a long meeting with the director of the Guggenheim Museum, Thomas Krens. It took place in his office and throughout the meeting his feet were literally in my face, firmly planted on his desk. I couldn't quite tell if this was a sign that he was comfortable or being cool, or if it was an odd power game. So I decided that for HoMu BKLYN, I would create an even more ambiguous set-up. I would appear to be doing nothing. But it's just a pose: I am very much aware of what's going on around me. I can sense people's reactions to what they see even with my eyes closed. I can feel if they are spooked, amused, or fascinated. It's a very powerful experience.

DI: There is also a comical aspect. You are wearing your fake beard, which makes you look like a demented bum, and you're lying in this huge white bed. Meanwhile, the audio tour beckons people to climb up a ladder and look at our noble trash, assembled into the so-called $0 Collection.

FN: Remember John Lennon and Yoko Ono's much publicized "bed-in for peace"? They were so serious about it. When you look at the footage today, you can't help laughing. Who were they kidding, advocating for world peace from a squeaky white apartment in the most luxurious building in New York City?

DI: As a performance, it was genius.

FN: It was the birth of Reality TV, completely choreographed and staged with cameras rolling and everyone involved cashing in. But that's another story. In my case, I am staying in bed to mock the image of the hard-working and committed museum director.

DI: What do you consider HoMu's biggest challenge at this stage?

FN: For one, we find it still very difficult to entice people to come out to Brooklyn and visit the Museum. We've had some very odd open houses where we expected several groups of up to 12 people who had made reservations but failed to show. I suppose all cultural institutions have to deal with this kind of thing, but I have to admit it can be very disappointing, especially because so much personal effort and commitment goes into this project, not to mention the fact that we never charge admission. The bigger challenge, ultimately, is to make sure that the intellectual background of my work doesn't get lost in the "funkiness" of the Museum. HoMu is a fictitious museum with many quirky elements, but, in the end, it is about a serious issue: the degradation of art through commerce.

DI: What's wrong with art generating money?

FN: It means that there has been a shift in priorities. The way we relate to art is only a reflection on how we relate to each other.

DI: Last year, David Rockefeller donated $100 million to the Museum of Modern Art. On the other hand, he also supported the Modern's new and highly controversial admission fee of $20. What was he trying to do?

FN: I think that the most generous board members of this country's prominent cultural institutions have lost sight of what museums were built for: to make art accessible to everybody. They have become carried away with building multi-million dollar fortresses for their collections, and there is a lot of ego and pride involved in the fundraising. But in a time when social issues like homelessness and rising housing costs are increasingly dividing communities into haves and have-nots, museums have a stronger social vocation than ever. Looking at art should never be just another consumer experience reserved for the affluent. Now most museums have outreach programs and discounts for students and seniors, but I get the sense that they are doing it begrudgingly, with a patronizing air. There is this sense of entitlement to get as much money as possible out of the public. That's when things go awry. Museums exist to serve the public, and they should be more aware of it. Businessmen may be important to run such costly institutions as museums, but let's not put the horse before the cart. It's about art, not money.

DI: Many people have a hard time categorizing something that doesn't have a price tag, because that's how our value system works.

FN: It all goes back to the eternal question: what is art? Does it need to have a high price tag to be valued? Does it need to be seen in a palace to be appreciated? And what do you take away with you after seeing it? Is it a "been there done that" experience, or is it a continuous reflection on who we are?

DI: As you explained, the Homeless Museum is essentially an institutional critique. But, true to its name, the subject of homelessness is a recurring theme within it.

FN: The homeless are the ones who pay the ultimate price for what is wrong in this society. They are at the end of the line, and at some point I identified with them, fearing I might end up like them. Several pieces shown at the Museum were inspired by the homeless. Some were even created with their participation. There is a series of white canvases signed by multitudes of homeless men and women I approached on the street; we are showing several self-produced video shorts that document their lives; and our membership program is geared to directly benefit the homeless.

DI: You once said that you identify "homelessness" among the wealthy as well as the poor. Can you explain what you mean by that?

FN: For me, the millionaire who is a compulsive shopper and hoards possessions is not so different from the bum who pushes a cart full of bags filled with trash. In a spiritual sense, he may be just as lost as the poor man who lives on the street. Both the bum and the millionaire create a sense of ownership with whatever means they have, because it gives them comfort. But when you're rich and caught up in the process of constant accumulation of property and goods, things get out of balance. Philosophically speaking, too much equals too little.

DI: There is a long tradition in the arts of institutional critique. Which artists would you name as influential for your own work?

FN: The two Marcels: Duchamp and Broodthaers. Duchamp for his unique way of mocking the art world while creating some of the most original works of his time; Broodthaers for creating the first fictitious museums to express his disenchantment with the cultural establishment. Our Museum Café is named after him, and the menu is a tongue-in-cheek homage to his work: We are serving cooked mussels (out of the shell) and hard-boiled, shelled eggs, alluding to his famous composites of mussel- and eggshells.

DI: Since every corner of the apartment is assigned to function like a museum, some visitors assume that even the most banal objects are either installations or have a symbolic meaning. At the last opening, a couple of visitors even asked me if the books in the Morgue and Library installation had been specifically acquired for the piece.

FN: That's funny. But in a way, they are right. Even though many of the things in the apartment have been there long before we opened HoMu BKLYN, they have taken on a new meaning since they have been incorporated into the Museum. The beauty is that our visitors, by their sheer presence, are affirming the very fact that everything in the apartment has effectively become part of an art installation. I encourage them to interpret any object they see within the context of a museum. In a way, we have not only created a museum within an apartment, but a museum that looks like an apartment. The lines are blurred, and the more the latter is affirmed by visitors, the more we can view HoMu BKLYN as a success. It reminds me of a long tradition in Flemish art that infuses religious symbolism into domestic environments. For example, in 15th century Flemish painting, the Annunciation was frequently set inside contemporary middle-class homes. Likewise, our apartment has become a stage, and visitors are breaking the fourth wall to become part of the artifice.

DI: Visitors also are confronted with a seemingly unresolved, ironic contradiction. Here they are, entering a two-bedroom apartment in one of New York City's most desirable neighborhoods, and it calls itself the "homeless museum.''

FN: People will have to go beyond the snap associations of the word "homeless." Once they make that leap of faith, everything here will make sense to them. I've seen it happen with many visitors.

DI: Tell us about new additions to HoMu's collection since its opening in 2005.

FN: I am most proud of the creation of MoMA HMLSS, a museum-in-a-suitcase that displays miniature versions of MoMA's highlights and proposes to be a mobile, free alternative to the exclusive Museum of Modern Art. It's on view in our Main Hall, but we have already taken it to Kansas City, Toledo (Spain), and Waterloo (Belgium). We also displayed it right across of the Modern's main entrance on the one-year-anniversary of MoMA's reopening. Florence Coyote was brought along for the occasion and caused quite a stir. We also have a new work inspired by one of today's most successful performance artists, Marina Abramovic. During her series of performances last year at the Guggenheim, she re-enacted an original piece of hers, Lips of Thomas, from 1975. The performance included self-mutilation on a cross, fashioned from ice blocks. I was able to salvage one of the ice blocks and brought it to HoMu, where I stored it in our freezer.

DI: Right next to our membership forms, which we keep in there, as well.

FN: Eventually, I decided to create a facial tonic for museum directors and curators out of drippings from this ice block. I call it Eau d'Abramovic, and the prototype is on exhibit in the Museum. Visitors are encouraged to test it. It is truly an homage to her à la HoMu.

DI: Does Marina know about this?

FN: Yes, and I am told that she got a kick out of it, which is great because it proves that she has a real sense of humor. I heard that she showed our Eau d'Abramovic press release around at a dinner party. Allegedly, MoMA director Glenn Lowry, who was also present, suggested she should sue me.

DI: I am not in the least surprised. It proves that Lowry is a bureaucrat without any sense of real imagination, not to mention humor. It is outrageous that someone like this should head one of the world's leading museums.

Talk about another new piece, Liquid Gold!

FN: We had a leak in our roof and, during a week of heavy rain, collected quite a bit of water in a bowl we placed under the leak. This water had a golden tinge, and I decided to present it as a sort of holy water sent to the Museum from above. What's more, the leak somehow closed itself off miraculously after a week, like a wound.

DI: That's almost enough to turn HoMu into a pilgrimage site!

FN: We filled the liquid into a glass carafe and displayed it on the windowsill, presenting it as an "anonymous gift" to the Museum.

DI: Speaking of gifts: HoMu has recently become a generous contributor for a good cause. Tell us about that.

FN: We have created our own Outreach Program. During my years as an educator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I was frequently sent out to conduct little art seminars in schools and community centers. Most museums have these so-called outreach programs, but they are never given proper financial support or time to really make a difference. Basically, they are fundraising tools. Museums promote them in a big way to receive donations that end up fueling the institution itself, not the meager programs. I decided to expose this practice. So we are doing community support by distributing home-baked sourdough bread. We bake it freshly every week, keep half of it for ourselves (it's delicious), and use the other half for the Outreach Program.

DI: You should mention who gets it.

FN: We feed pigeons in the city's parks with it.

DI: Some people might wonder why you don't feed the homeless with it?

FN: If HoMu were a real institution, that would be precisely what it would do. Just imagine the press report: "The Homeless Museum provides NYC's poor with home-baked bread!" As it happens, HoMu is a satirical art project, and we are not interested in glorifying ourselves by being seen as generous benefactors.

DI: You've been living in America for half your life. Which American artists would you name as influential for your work?

FN: There is an endless list of American artists I admire greatly, but I couldn't tell how they directly affect my work. Still, I recently reacquainted myself with the works of Robert Smithson, who had a retrospective at the Whitney last summer. His criticisms about museums confirmed my own sentiments. He once stated that museums are "tombs", and that "visiting a museum is a matter of going from void to void." In the Seventies, when he made that statement, museums really were like tombs: they seemed stale and remote. Today, they are more like glorified shopping malls, which I find worse.

DI: How do you come up with ideas?

FN: It's a left-brain, right-brain kind of thing. Sometimes, when the idea for a new piece comes to me, it first seems like an arbitrary combination of unrelated elements. But, as I start working on it, connections reveal themselves. For example, our so-called "Morgue & Library" is more than a pun on the famous Morgan Library in New York City. While the Morgan Library is a place of selective memory dedicated to precious manuscripts and books, the Morgue & Library is a memorial of sorts dedicated to the homeless and art. The "morgue" element came about in response to a report on a homeless man who was crushed to death when he was accidentally picked-up by a garbage truck. Thus I created this installation that consists of two small, corpse-like figurines displayed on a light box above a bookcase filled with art books.

DI: Do you think that the fact that you were raised in several countries as a son of a Belgian career diplomat had an impact on your affinity to homelessness?

FN: All diplomats are homeless. They are being sent around the world to represent something that becomes more and more remote the longer they are on the job. They have to learn to carry their sense of home within them. So, yes, it definitely plays a role.

DI: You made New York your home 20 years ago: what's the connection between HoMu and the fact that you live here?

FN: The Homeless Museum could not have been created anywhere else. For one,

I've been appalled by the omnipresence of homeless people in New York City ever since I moved here, and I felt the need to articulate it in my work. But, in addition to that, there is a much more personal connection. A few years ago, I had an epiphany when I realized that I spent my entire time just struggling to get by, doing a job where I didn't feel appreciated and that I didn't particularly care for either.

DI: You were teaching French in an exclusive private high school run by closeted gay Jesuits and a back stabbing nun. You had taken on the job to get out of debt after you lost your job at the Met Museum.

FN: I stuck it out for three years. I was dreading this way of life so much that I found myself eyeing homeless people, wondering if homelessness was the only other option for me. This is when I started making art again in earnest, as a way to deal with my fear of becoming homeless.

DI: Eventually, you found the courage to quit your full-time job and devote your time to what you wanted to do more than anything, making art.

FN: But I never stopped lecturing for colleges and museums, and this is where I drew my inspiration to create a fictitious museum that would address the politics of established cultural institutions.

DI: So, HoMu really fuses two dominating aspects of your life: fear of failure and your love of art.

FN: I think that this fear of failure is just as much part of the American psyche as the "American dream." In America, homelessness really begins at home; what you see on the streets is only the surface of it.

DI: Some people dismiss HoMu BKLYN as an entertainingly goofy, frivolous freak show. Does this hurt you?

FN: I am all for bringing humor into the field of art, and there is definitely not enough of it out there. But my intent is not to entertain the crowds but to prove that art can be experienced free from commerce, media hype and imposing architecture. That's anything but frivolous.

DI: I always compare you to Till Eulenspiegel, the legendary prankster from the medieval ages. He always told the truth, but in a twisted way.

FN: Personally, I am very fond of these lines by Emily Dickinson: "Tell all the truth but tell it slant," and "The truth must dazzle gradually or every man be blind." She was, by the way, virtually unpublished during her lifetime. People tend to forget that success stories are not all there is to art.

DI: Well, everybody knows about Van Gogh's poverty and misery.

FN: Yes, but how many Van Goghs has this world had that didn't get discovered, even posthumously? It's a frightening thought. Imagine how much human suffering and energy went to waste.

DI: It's out of our hands. We can only continue and try to do good work. So what are you working on right now?

FN: I am developing two projects with Grand Arts, a non-for-profit arts organization in Kansas City. Next month, I will present HoMu Cribs, a recreation of HoMU BKLYN, displayed exclusively in select private homes. On June 18, I will be hosting a walking tour that will connect the various "cribs" and invite participants to celebrate this birth of a new "homeless museum" in Kansas City. HoMu Cribs is basically a way to introduce the Homeless Museum in KC. It's a one-day experiment, and if it works, we'll try to do the something similar here in New York.

DI: Tell us about the other project you are developing with Grand Arts.

FN: For a year now, we've been discussing the realization of the New Homeless Museum or NHoMu, the first museum built without architecture. Its inauguration is scheduled for Spring 2007.

DI: Explain the emphasis "without architecture"!

FN: I am very irritated by what architects have done to museums in recent years. With very few exceptions, most museum architects have simply been unable to create adequate homes for art. Instead, they have given in to the temptation to upstage the art and draw the main attention to themselves, hence the phenomenon of the star architect. The results are catastrophic, and we are going to have to live with them for a very long time. The New Homeless Museum is a direct attack on that.

DI: What will NHoMu look like?

FN: NHoMu will consist of a massive block of soap: 75 tons of orange glycerin soap resting on a platform. Visitors will be invited to literally carve into the structure to create interior spaces or "galleries." The elements will contribute to the museum's disintegration as well. Eventually, the site will be cleared entirely, and nothing of the original structure will remain after 90 days.

DI: Why did you choose soap as a building material?

FN: The sad fact is that museums are dirty businesses - from tomb robberies to money laundering, to the manufacturing of exclusiveness, etc. We need to purge ourselves. NHoMu will be distributed to its visitors to "spread the message."

DI: I know that a recent visit to Christie's spawned a new idea of yours...

FN: The Donald Judd Foundation decided to auction off 25 Judds to raise money, and, for the week preceding the auction, the works were on view at Christie's. Interestingly, Judd, who died in 1994, is quoted in the auction's catalogue as saying that his works are "not made to be property, not on the market, not for sale." After seeing the exhibit, I toyed with the idea of creating a miniature version of it as another collection-in-a-suitcase, like MoMA HMLSS. It was going to be a private memento of this once-in-lifetime exhibit at Christie's, and I was going to call it "Carry-on Judd." Then I went to the auction. It was fascinating and shocking at the same time. By the slam of a hammer, the Judd pieces were downgraded to expensive eye-candy millionaires would soon show off with and brag about. This is exactly what Judd tried to avoid, but time and the development of the art market have overruled him. I decided then and there that my miniature replicas of the Judd pieces would be made out of chocolate.

DI: But by creating replicas of originals aren't you also exploiting Judd's work?

FN: It's not like I'm going to throw Judd-style chocolate truffles on the market! I'm doing this to show what is already going on out there. I'm just bringing it one step further to unveil the absurdity of it all.

DI: To sum it up, can we say that you are an artist whose work is about creating new museums, fictitious or real?

FN: I have created a museum in a home (HoMu BKLYN), and a museum in a suitcase (MoMA HMLSS). Next month, I will unveil a museum that will exist for only one day (HoMu Cribs), and next year I will launch my "incredible shrinking museum" (NHoMu).

DI: Where do you go from there?

FN: I have this idea for an airborne museum. It will forever expand, like a soap bubble.